For He’s a Jolly Good Fellow?

The wind was bitingly cold up at four thousand metres on the Tibetan plateau, and the air thin enough to make my scramble up the stony hillside feel like an epic feat of mountaineering. I was quite light-headed by the time I finally reached the fort at the top, and at first thought it must be this that was impairing my vision. But rubbing my eyes and getting my breath back still made no difference: the red and gold sign in front of me really was announcing “The Memorial Hall of Anti-British”. Surely this must be a mistranslation of what was written above in Tibetan and Chinese, I mean nobody would set up a museum with the sole aim of criticising my country - would they?

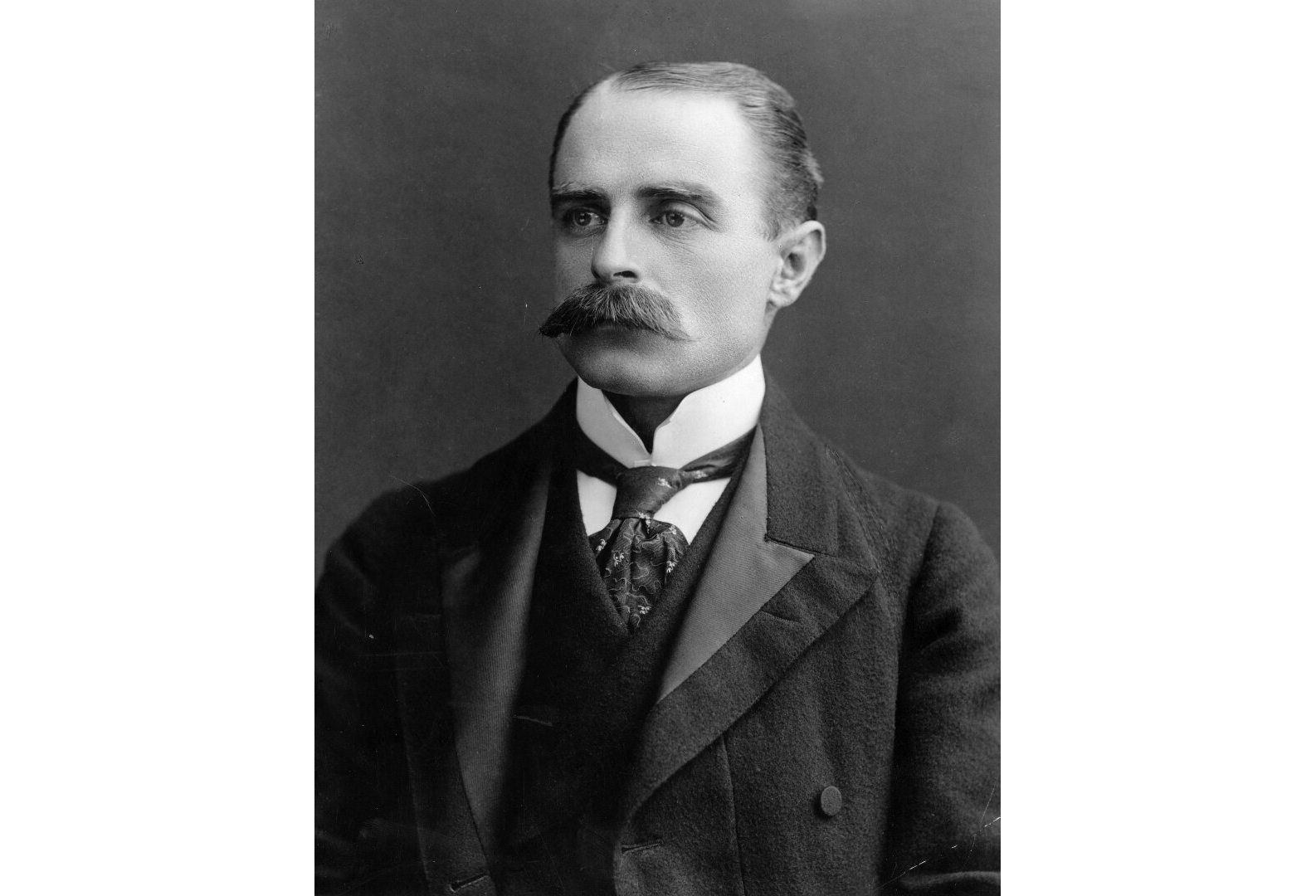

Twenty minutes later, I had reversed this opinion as well as greatly improved my knowledge of Tibetan history. The two rather shambolic rooms I’d just emerged from were dedicated to the 1904 invasion of Tibet led by a British army officer, Sir Francis Younghusband. In one particularly brutal incident that occurred nearby, he had set his machine guns on Tibetan monks armed only with sticks and swords, slaughtering some five thousand of them. British casualties in the encounter meanwhile stood at five. I could now see where the inspiration for that sign might have come from.

By the time of this massacre, Sir Francis was already a seasoned traveller, best known for a series of death-defying treks across the Himalayas and the Hindu Kush, drawing the first detailed maps of these remote areas along the way. His exploits led to him becoming the youngest ever Fellow of London’s Royal Geographical Society at the tender age of just twenty four. Fast forward a few decades, and he had risen to become its President.

Today, the Society is housed in a rambling Gothic pile adjacent to Hyde Park in one of London’s poshest postcodes, as befits the world’s premier explorers’ club. It has been the launchpad for some of the most epic adventures of the last two centuries, including David Livingstone’s nineteenth century expeditions to Africa (he of the “Doctor Livingstone, I presume?” fame), Charles Darwin’s maritime odysseys that shaped his theory of evolution, Ernest Shackleton and Robert Scott’s ill-fated travels to the Antarctic, and Sir Edmund Hillary and Tenizng Norgay’s summiting of Mount Everest.

The Society began in the early nineteenth century as a dining circle for over-privileged white men, meeting up to discuss travel and science. It acquired its “Royal” moniker in 1859, when Queen Victoria gave it her blessing. This thumbs up from the monarchy was partly due to the organisation’s increasing usefulness as a source of maps and intelligence about little-known lands, at a time when exploration often went hand-in-hand with exploitation. Explorers’ findings were eagerly awaited by those in power to ascertain which new discoveries might be exploited for their own gain, always under the guise of promoting the three C’s of civilisation, Christianity, and commerce of course. Even the Society’s own website acknowledges that its history “was closely allied for many of its early years with colonial exploration in Africa, the Indian subcontinent, the polar regions, and central Asia”. This colonialist bent was also reflected in its choice of Presidents which, in addition to Sir Francis, included Lord Curzon, the Viceroy of India and later the British Foreign Minister.

These days, however, the Society’s much more friendly modus operandi is “to promote and support the discovery and understanding of the world’s people, places and environment”. In line with this, it supports research and expeditions across the globe, as well as putting on really rather interesting talks and exhibitions. It also houses a massive library containing a couple of million books, documents, and photographs, along with one of the world’s largest map collections. This reform in approach is reflected in its recent choice of Presidents. In 2009, for example, former Monty Python comedy troupe member and traveller extraordinaire Michael Palin was sworn into the role, a man about as far away from Lord Curzon as you could hope to get.

It took me twenty more years than Sir Francis to clock up enough miles to make the Society’s grade and be appointed a Fellow in 2021. Though I had no inkling at the time that I’d also one day be asked to step on to its hallowed stage myself, following in those intimidating footsteps of Livingstone, Darwin, Shackleton and Hillary to talk about, of all things, my search for the yeti.